While the government has set an ambitious target for ethanol-biodiesel blending, the volatility in ethanol production volumes has disrupted these plans. The goal of achieving a 5% biodiesel blend in diesel sales by 2030 now appears unrealistic. As a result, the government is considering blending biodiesel with used cooking oil (UCO). The initiative to repurpose used cooking oil (RUCO) was launched in 2019.

Biofuels are biodegradable fuels derived from vegetable oils, animal fats, or recycled cooking oil. Its current popularity was once overshadowed by the belief that electric vehicles (EVs) would dominate the market, reducing the need for further R&D in biofuels. However, the industry has since recognised that no transition method is entirely clean, and biofuels have returned to the spotlight, with high hopes for their role in reducing carbon emissions.

READ | Food inflation threatens to upset India’s economic stability

Biofuels are preferred over EVs because transitioning to electric vehicles requires replacing existing internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles and supporting infrastructure, which is capital-intensive. EVs also depend on batteries and critical minerals, which are largely imported, raising environmental concerns about the mining processes involved, among other issues.

In contrast, biofuels can be used in existing ICE engines and infrastructure with minimal modifications (depending on the blending rates), and they offer greater energy independence.

India’s biofuel goals

In India, biofuel primarily refers to first-generation (1G) ethanol, which is mainly sourced from food crops. The policy target of achieving 20% ethanol blending with petrol (E20) by 2025-26 is likely to be met almost entirely by 1G ethanol made from sugarcane and food grains. Second-generation (2G) ethanol, derived from crop wastes and residues, is not yet a reliable source due to limited feedstock supply chains and difficulties in scaling up. It is important to note that “biofuel” is a blanket term encompassing both sustainable and unsustainable fuels. Simply scaling up biofuel production without ensuring decarbonisation will be futile.

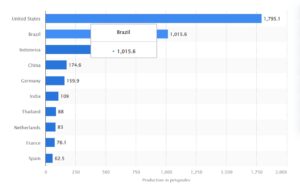

Leading countries based on biofuel production worldwide in 2023

To meet its target of 5% biodiesel blending, as outlined in the National Policy on Biofuels (2018), the government introduced policy measures such as tax reductions and price incentives, including a reduction in the Goods and Services Tax (GST) rate for biodiesel and offering remunerative prices for procurement. An amendment to the National Policy on Biofuels in 2022 reaffirmed the 2030 deadline, when the government tentatively plans to begin direct sales of biodiesel in the country.

Despite these efforts, biodiesel blending in diesel fuel has progressed slowly in India. Even with the procurement of over 980 million litres of biodiesel since 2015, the blending rate was only 0.1% in August 2021, reaching just 0.8% by the end of 2023-24.

To ensure a steady supply of biofuels, India needs to ramp up production of raw materials such as sugarcane. However, this comes with hidden environmental costs. While the connection between sugarcane cultivation and groundwater depletion is well understood, the impact of using food grains for ethanol production on food security is less apparent due to India’s current surplus in food production.

This surplus may not persist in the future, as global warming is projected to stagnate crop yields worldwide. A recent study led by the University of Michigan projected that groundwater depletion rates could triple during 2040-81 compared to current levels. Multiple challenges, including the limited availability of feedstock, non-edible oilseeds, animal tallow, and acid oil, already threaten ethanol production.

As countries face the dual challenges of feeding growing populations and shrinking arable land, food security will take precedence over energy generation. This makes India’s reliance on surplus production for ethanol blending a risky strategy.

While biodiesel is touted as a saviour, experts have also highlighted that the agricultural sector is a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. Diverting agricultural resources toward fuel production to reduce emissions from the transport sector creates a counterproductive cycle with minimal overall environmental benefits.

Future of biodiesels

As countries become more aware of the hidden costs of biodiesel, the Global Biofuels Alliance, formed at the G-20 Summit in New Delhi, is pushing for the development of “sustainable” biofuels produced from crop residues and other wastes, with low water and GHG footprints

As India becomes the world’s third-largest ethanol producer, it must address challenges in securing a sustained ethanol supply for biodiesel while considering the environmental impact.

India should also consider incentivising a reduction in sugar cultivation rather than diverting the surplus to ethanol production. Efforts should focus on promoting 2G ethanol, which could be considered a sustainable fuel, especially if crop residues do not need to be transported over long distances to a central manufacturing plant. Additionally, agencies like the Global Biofuels Alliance must promote innovation and technology development to establish an efficient biomass supply chain and smaller-scale, decentralised biofuel production units.