The Reserve Bank of India faces a dilemma at the ongoing monetary policy committee meeting. With inflation well within the tolerance band and forward-looking projections indicating a further decline, there is a compelling case for a 25 basis point cut in policy repo rate. However, there are various reasons —ranging from global volatility to concerns over financial stability—why the RBI needs to exercise caution.

It is widely expected that the RBI will announce its first repo rate cut in five years. The move would complement fiscal measures outlined in the recent Union Budget 2025-26 aimed at boosting consumption-led growth. Inflation is within the central bank’s comfort zone, with projections trending towards 4.5%, while high borrowing costs have dampened investment and private consumption. However, concerns remain over the rupee’s depreciation and global economic uncertainties. Many economists advocate a gradual easing cycle, with a 25 bps cut now potentially followed by another in April. The decision will be a test for newly appointed RBI Governor Sanjay Malhotra as he balances economic growth imperatives against financial stability risks.

READ | India’s transfer pricing reforms could ensure better compliance

Why a repo rate cut

Reports indicate that the current real repo rate is above 2%, a level that historically contributed to investment slowdowns in India, most notably in the 2010s. This suggests that high real interest rates are suppressing aggregate demand. Corporate results are already reflecting a slowdown, and maintaining persistently high real rates could have long-term adverse effects, given that monetary policy acts with a lag.

Inflation has moderated, with expectations for January at 4.6% and for the year at 4%. Even if we consider temporary price fluctuations in key commodities like tomatoes, onions, and potatoes, underlying inflation remains within range. Historically, inflation targeting has been a key RBI mandate, but when inflation is comfortably within limits, monetary policy must pivot to supporting growth.

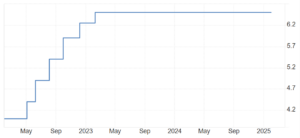

RBI’s policy repo rate

Contrary to the argument that the Union Budget provides enough stimulus, fiscal consolidation is actually reducing net government demand. Market borrowings for the next year are set at 3.2% of GDP, slightly lower than the current year’s 3.3%. While interest payments remain high, the overall fiscal stance does not negate the need for monetary support.

Many central banks have already started cutting rates despite inflation not always being at target levels. India, with its strong long-term growth potential, is unlikely to experience a capital flight due to a moderate rate cut. Additionally, foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) are more attracted to robust economic growth than to artificially high interest rates.

While some economists argue that liquidity is a more pressing concern than rates, RBI has demonstrated that it has the necessary tools to manage liquidity effectively. A rate cut would complement these efforts, boosting credit demand and ensuring a sustainable growth trajectory. Banking sector performance has been strong, and lowering real rates would further improve loan demand and repayment capacity.

Arguments against a rate cut

One major argument against a rate cut is the uncertainty in global financial markets. With the US Federal Reserve maintaining its pause, any rate cut by the RBI could weaken the rupee, making India more vulnerable to capital outflows. However, India’s external position has remained resilient, and the rupee has already adjusted to market movements, mitigating concerns of external shocks.

Despite recent RBI interventions, core durable liquidity remains in deficit, and overnight rates have been exceptionally high. Cutting rates before ensuring adequate liquidity could be ineffective. However, the RBI has demonstrated its ability to provide liquidity support when needed, and liquidity measures can be implemented alongside a rate cut to maximise monetary transmission.

With elevated credit-deposit ratios and ongoing adjustments in liquidity regulations, some caution against rushing into a rate cut. However, ensuring financial stability does not mean keeping rates high indefinitely. A measured 25 bps cut now, followed by another later in the year, would provide a balanced approach to supporting growth without causing undue disruption.

Why a cut makes sense

Balancing all factors, a 25 bps repo rate cut in February is both a prudent and necessary step. The combination of moderate inflation, fiscal consolidation, high real interest rates, and a sluggish investment environment warrants monetary support. While global uncertainties and liquidity challenges remain, these can be managed through complementary policy measures.

Further, historical experience shows that prolonged high real interest rates constrain aggregate demand and investment. Given the lagged effects of monetary policy, waiting until April risks missing the window for timely intervention. A moderate rate cut now, possibly followed by another later in the year, would signal RBI’s commitment to ensuring stable, sustainable growth without compromising financial stability.

However, some economists suggest that the RBI should wait for more stability and implement a larger rate cut in April rather than making a staggered cut now. While this approach has merit, delaying rate cuts could further dampen investment sentiment, particularly when the economy is already facing growth headwinds.