The GST Council is expected to outline a roadmap for the continuation of the compensation cess, which is likely to extend well into 2025-26. Key discussions in its meeting scheduled for September 9 will revolve around whether the compensation cess should be replaced by a tax or another form of cess. However, it is equally important for the Union government to address the issue of revenue sharing with state governments.

The compensation cess has been a point of contention in the ongoing Centre-state dispute over GST revenue sharing. When the GST regime was implemented on July 1, 2017, states were initially assured compensation for any revenue losses until June 2022. To cover revenue shortfalls during the pandemic years (FY21 and FY22), the Centre extended the compensation cess on luxury, sin, and demerit goods until March 2026. Between July 2017 and July 2024, the net collection from the GST Compensation Cess amounted to ₹7.61 trillion, with projections estimating this figure will reach ₹8.6 trillion by March 2025.

READ | Farm sector needs sustainable solutions for survival

The Union government contends that despite rising GST collections, the compensation account is projected to fall as of March 31, 2025. This is attributed to factors such as back-to-back loans, interest payments, and other expenses. As a result, the compensation levy is likely to continue beyond FY25 and well into FY26.

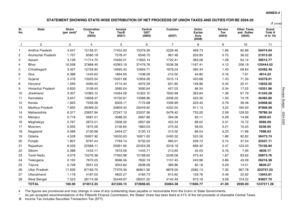

States, on the other hand, have seen growth in their protected revenues, which have risen at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14% since GST’s introduction. However, cess collections have not kept pace, and the revenue gap widened due to the pandemic-induced decline in cess collections. Moreover, cess and surcharges collected by the Union government, which make up approximately 23% of gross tax receipts for 2024-25, are not part of the divisible pool and, therefore, not shared with the states.

A status report will be presented to the GST Council on the compensation cess, including a timeline for repaying the Rs 1.1 trillion borrowed by the Centre in FY21 under a special window and passed on to the states.

Beyond GST compensation cess

Several opposition-ruled states, particularly in southern India, have accused the Centre of not providing a fair share of transfers under the current financial devolution scheme. These states argue that their contributions to tax collections far exceed the revenue they receive in return.

States like Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu have repeatedly voiced dissatisfaction over the allocation of tax revenues. This financial strain has been particularly acute during election periods when spending on social welfare schemes becomes a priority, and states’ own tax and non-tax revenues grow sluggishly. As a result, states are left protesting the perceived inequity in their share of union taxes, grants, and loans from the Centre.

The formula for calculating each state’s share of tax revenue, including corporation tax, personal income tax, Central GST, and the Centre’s share of the Integrated GST (IGST), is based on the recommendations of the Finance Commission, which is constituted every five years. The divisible pool, however, excludes cess and surcharges levied by the Centre.

Currently, states receive 41% of the divisible pool (vertical devolution), with distribution among states (horizontal devolution) determined by factors such as per capita income, population, forest cover, demographic performance, and tax effort. Equity (income disparities) and need (population, area, and forest) are given more weight than efficiency (demographic performance and tax effort).

While political disagreements are inevitable, the issues raised by states regarding the current system deserve attention. Experts have also questioned the Finance Commission’s formula, which they argue incentivises states that have not controlled population growth or achieved rapid economic growth. Federalism is a cornerstone of India’s governance, and it is crucial that states do not feel unfairly treated in terms of resource allocation. Notably, the share of southern states in the divisible pool has declined over the last six Finance Commissions.

The way ahead

The Finance Commission must address the imbalance, where states generate approximately 40% of revenue but shoulder around 60% of expenditures. A fairer sharing mechanism should be proposed to ensure equitable development across all states. Experts have also advocated for widening the divisible pool to include a portion of cess and surcharges.

Another solution would be to gradually phase out various cesses and surcharges by rationalising tax slabs. Over the past decade, the Union government has introduced numerous new cesses and surcharges. While GST was expected to subsume many of these levies, new ones have emerged, and old ones remain outside the GST framework. For instance, the Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess was introduced in FY22, and the Health and Education Cess, introduced in FY18, replaced the earlier Primary and Secondary Education Cess on direct taxes.

The proliferation of cesses and surcharges has resulted in a growing portion of gross tax revenue being excluded from net proceeds.

The Finance Commission must now take proactive steps to correct historical imbalances in vertical devolution and ensure compensation for states. Additionally, lump sum untied grants should be provided to address any shortfalls in devolution that may have occurred over the past decade. The 16th Finance Commission’s stance on vertical devolution will be critical for upholding the principles of fiscal federalism in India.