India is one of the signatories of the Brasilia Declaration on Road Safety, which was signed during the second Global High-Level Conference on Road Safety in Brazil in November 2015 by Union Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari. The declaration aimed to halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic crashes by 2020.

This target was also incorporated into the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which began implementation on January 1, 2016. Target 3.6 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aims to halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents by 2030, using 2016 as the baseline year. Originally, the target was set for 2020, but due to slow progress, it was extended to 2030. Despite a slight reduction in deaths globally since 2016, progress has been limited, even as the global motor vehicle fleet has more than doubled.

READ | NITI Aayog’s challenge: From command and control to cooperative federalism

The Indian Scenario

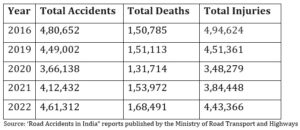

In 2016, a total of 150,785 people were killed according to the “Road Accidents in India-2016” report published by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. By 2022, this number had increased to 168,491, marking a 9.4% increase in fatalities compared to the previous year. This rise in fatalities, despite a reduction in accidents, indicates an increase in the severity of these accidents. Data for 2023 is still awaited. The following table provides a clear picture of the number of road accidents, deaths, and injuries over the last few years, starting from the baseline year of 2016.

Table 1

After the Lok Sabha rejected the Road Transport and Safety Bill in 2016, the existing Motor Vehicles Act (1988) underwent significant overhauls, culminating in the President of India’s assent on August 9, 2019, following the passage of the amendment bill by both houses of Parliament. This marked the end of a five-year process.

The highlight of the Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act, 2019, is the substantial increase in penalties as a deterrent for serious road traffic violations. When the act came into effect in September 2019, there was widespread concern among road users about the enhanced penalties.

In Haryana and Odisha, the police collected more than ₹1.41 crore in penalties within four days of the Act’s implementation. In Delhi, there was a 20% increase in applications for the renewal of driving licenses. These are a few visible outcomes. However, this fear was short-lived. Due to political considerations, the States undermined the implementation of this Act. Fearing resistance from road users, many state governments delayed the notification of the Act, reduced the enhanced penalties, or put the implementation on hold, keeping in mind upcoming elections.

Failed Enforcement Raises Concerns

In a federal system like India’s, enforcement is entirely the responsibility of the State Governments. However, the States have failed to implement the Act effectively. Since traffic laws are not strictly enforced, drivers feel they can get away with committing serious violations, leading to a culture of non-compliance.

According to the 2022 report, the main reasons for violations, such as speeding and driving on the wrong side of the road, are due to a lack of enforcement. Over-speeding remains the leading cause of accidents, accounting for 72.3% of all accidents in India and over two-thirds of all deaths and injuries.

Around half of the 16,715 people who died in accidents were passengers, and over 42,000 suffered injuries because they were not wearing seat belts. Similarly, out of the 50,029 motorcycle/scooter riders who died in accidents due to not wearing helmets, over 14,000 were pillion riders. A total of over 100,000 people were injured for the same reason.

Culture of Non-Compliance

Between 2020 and 2023 (until March), traffic offences resulted in challans amounting to ₹3,793 crores. However, only ₹269 crores were collected, a mere 7.1%. Speed limit violators across the country paid nearly ₹110 crores in fines in 2022, but ₹729 crores remained unpaid. In the top five States/UTs (Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chandigarh, and Haryana), the total pending fines for speed violations amounted to ₹701 crores, with Delhi having the maximum due of ₹550 crores.

Some state governments have implemented measures like fast-track courts and automatic number plate recognition systems to reduce the backlog and ensure timely enforcement. Between 2019 and 2023, the Mumbai Traffic Police collected ₹579.9 crores in e-challan fines. However, during the same period, ₹685 crores remained pending. Mumbai Police have issued notices to defaulters, and those failing to pay are being charge-sheeted before courts. As a last resort, warrants are issued if the person fails to appear in court. This strategy yielded results: between January and October 2023, Mumbai Traffic Police recovered fines amounting to ₹205 crores.

The Delhi transport department has decided that traffic fine evaders with more than five pending challans will not be able to go online to register changes of vehicle ownership, obtain a vehicle fitness certificate, or access other services through the government portal. These types of campaigns and measures need to be replicated in other cities and states to ensure compliance.

Apathy of State Governments

In most states, the Road Safety Cell within the Department of Transport is the lead cell for road safety and the focal point linked with the Supreme Court Committee on Road Safety (SCCoRS). However, this cell lacks statutory powers to ensure better coordination between various departments and agencies related to road safety and road management, such as the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI). In addition to the Road Safety Cell and District Level Road Safety Committees, as per Section 215 of the Motor Vehicles Act, there are multiple committees and councils at the state level dealing with road safety in most states.

This points to the need for a single agency to coordinate and manage all road safety-related affairs—a State Road Safety Authority—for effective implementation of the Motor Vehicles Act. This authority would deal with all matters related to road safety, formulate effective plans of action, policies, schemes, projects, and programs for strengthening road safety in each state, and coordinate with stakeholder departments and agencies to discharge duties related to road safety. As of now, only a few states, including Kerala, Karnataka, and Gujarat, have such authorities.

In the absence of a national plan of action, there is a lack of consistency in initiatives, particularly when there is a regime change in the states. For example, during the budget speech in 2023, the then Chief Minister of Rajasthan announced the setting up of district road safety task forces with allocated budgets to achieve the target of reducing road accident mortalities by 50% by 2030. Task forces were subsequently set up in each district, resulting in a reduction in road accidents in some districts of Rajasthan. However, the current regime has abandoned these initiatives and developed another 10-year road safety action plan aimed at reducing deaths in road accidents to zero.

Plan on Road Safety 2025-2030

Similar to the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030, with a target to reduce road deaths and injuries by 50% by 2030 at the global level, India needs to have an “India Plan of Action on Road Safety 2025-2030” to achieve the ambitious target of preventing at least 50% of road traffic deaths and injuries by 2030. However, such a plan is currently missing.

India urgently needs a “Plan of Action on Road Safety 2025-2030” to make progress toward this goal, with year-by-year targets, indicators, milestones, and rigorous monitoring of progress and corrective action.

The Plan of Action should align with the Decade of Action for Road Safety by emphasizing the importance of a holistic approach to road safety, focusing on continued improvements in road infrastructure and conditions, law enforcement and legal amendments where needed, and the provision of timely, life-saving emergency care (trauma care) for the injured. The Plan of Action should also promote sustainable mobility. There is an urgent need to prepare such a plan, involving all states and key stakeholders.

Without a comprehensive Plan of Action on Road Safety, along with time-bound implementation, rigorous monitoring, strong political will, and commitment, achieving the ambitious target of halving road fatalities by 2030 will remain a distant dream.

George Cheriyan is Director of Centre for Environment and Sustainable Development India, a national NGO in Special Consultative Status with UN-ECOSOC, and accredited with UNEP & UN ESCAP. CESDI is also a member of South Asia Network on SDGs.