India’s efforts to reduce poverty over the last decade have yielded impressive results. According to the World Bank, extreme poverty—measured at $2.15 per day in purchasing power parity terms—fell from 16% in 2011-12 to just 2.3% in 2022-23, lifting 171 million people above the internationally comparable poverty line. Rural and urban destitution levels have declined sharply, and the gap between them has narrowed substantially. Yet, behind these heartening numbers, serious questions of sustainability, inequality, and data reliability loom large.

The numbers are indeed spectacular. Rural extreme destitution fell from 18.4% to 2.8%; urban extreme poverty from 10.7% to 1.1%. The much-lamented rural-urban divide has narrowed substantially, with the gap reducing from 7.7 to 1.7 percentage points. Using the $3.65-per-day line, appropriate for lower-middle-income countries, the share of the population living in poverty fell from 61.8% to 28.1%, lifting 378 million people. This transformation is no less than a silent revolution.

READ | NPCI’s Netbanking 2.0 looks to replicate UPI success, but challenges loom

Falling poverty amid concerns over data integrity

As any discerning economist would remind us, the measurement of poverty is as much about methodology as it is about numbers. The World Bank itself admits that the comparability of consumption data over time is challenged by changes in survey design and sampling in the 2022-23 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey. Former Planning Commission secretary NC Saxena has rightly cautioned that unless destitution estimates are triangulated with independent sources such as the Census or the National Family Health Survey, our conclusions will remain suspect. The triumphalism must therefore be tempered with methodological humility.

Consider the broader picture. On the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)—which includes non-monetary dimensions such as education, living standards, and basic services—India’s progress is equally impressive. Multidimensional poverty fell from 53.8% in 2005-06 to 16.4% in 2019-21, and further to 15.5% in 2022-23. A staggering 415 million Indians have escaped multidimensional poverty over the past 15 years, according to the United Nations. Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh—long laggards in human development—have shown the most rapid improvement.

The State Bank of India’s latest report paints an even rosier picture: destitution has fallen below 5% nationwide, with rural poverty at 4.86% and urban destitution at 4.09% in FY24. If sustained, this places India among a small group of countries that have decisively beaten back extreme poverty.

How was this achieved? The answer lies in a confluence of factors: robust economic growth, targeted welfare interventions, improvements in basic amenities, and a gradual shift from subsistence agriculture to diversified rural livelihoods. Schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (housing), Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (sanitation), Saubhagya (electricity), and the expansion of food subsidies played critical roles. The economic momentum also helped: despite setbacks like demonetisation and the pandemic, India’s real GDP has grown at an average rate that most emerging economies can only envy.

Yet, even as we celebrate, three concerns must occupy policymakers’ minds.

Inequality and precarious employment

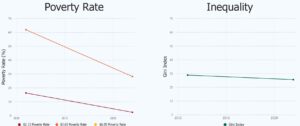

First, inequality. While consumption inequality, as measured by the Gini index, appears to have declined—from 28.8 to 25.5 between 2011-12 and 2022-23—the World Inequality Database tells a different story: income inequality has risen sharply. The Gini coefficient of income inequality increased from 52 in 2004 to 62 in 2023. The top 10% of earners have median incomes 13 times that of the bottom 10%. If unchecked, such divergence can undo the gains of poverty reduction, sowing seeds of social unrest.

Second, employment quality. Employment has indeed grown faster than the working-age population since 2021-22, but the structure of employment remains fragile. Only 23% of non-farm paid jobs are formal; agriculture continues to rely on informal labour; self-employment is rising but often disguises underemployment. Youth unemployment, particularly among graduates, remains alarmingly high at 29%. Gender disparities persist, with 234 million more men than women in paid work. In short, poverty has declined, but precariousness remains.

Third, data reliability. As the World Bank and experts like Saxena caution, changing survey methods mean that longitudinal comparisons must be made cautiously. The poverty lines themselves are in flux: adopting the updated 2021 PPPs would push the extreme poverty threshold to $3 per day, raising India’s poverty estimate to 5.3%. As the thresholds rise, the picture may not appear as celebratory.

This brings us to a deeper reflection: has India merely shifted the poverty line or has it created lasting pathways out of poverty? Access to cooking fuel, sanitation, bank accounts, and schooling certainly expand capabilities. But unless these improvements are matched with meaningful enhancements in health outcomes, learning levels, agricultural productivity, and urban employment opportunities, today’s escapees could become tomorrow’s returnees.

Moreover, poverty is not merely an economic condition; it is a deprivation of voice, dignity, and opportunity. Hence, the success of India’s poverty reduction must be judged not only by statistics but by how much it has empowered the poorest to participate meaningfully in economic and civic life.

From escaping poverty to building prosperity

To secure the gains, India must double down on investments in human capital—especially health and education. It must foster rural non-farm employment, modernise agriculture, promote formalisation of jobs, and strengthen social protection systems. Above all, it must recognise that poverty reduction and inequality reduction are not sequential goals—they must be pursued simultaneously.

India stands today at a unique inflection point. Having brought hundreds of millions out of destitution, it now faces the harder task of preventing their relapse and ensuring upward mobility. It is easier to pull a man out of the pit; harder to ensure he climbs the hill.

The silent revolution against poverty deserves celebration. But complacency is the enemy. If India can marry growth with equity, prosperity with inclusion, and policy ambition with institutional capacity, the tryst with destiny that Jawaharlal Nehru spoke of may at last be fulfilled—for every Indian.