As the strategic significance of semiconductors deepens globally and nations scramble to secure resilient supply chains, India is pushing hard to build a competitive domestic semiconductor industry. The government, underlining its commitment to this critical sector, has stepped up both policy support and financial incentives.

S. Krishnan, secretary at the ministry of electronics and information technology (MeitY), recently reaffirmed the government’s resolve to back the sector with sustained investment and support in the coming years. Semiconductor chips are the bedrock of the digital economy, enabling everything from smartphones to satellites. Recognising this, India has joined the global race to establish homegrown capabilities in chip design, manufacturing, and assembly.

READ | Clash of the titans: Trump tariffs could hurt America more than China

Like several other countries, India has rolled out a generous incentive package aimed at attracting global chipmakers. The production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes and a host of other policy measures have already begun yielding results, with multiple large-scale projects getting the green light. While earlier initiatives were largely targeted at startups and MSMEs, the government now seeks to draw in major industry players as well.

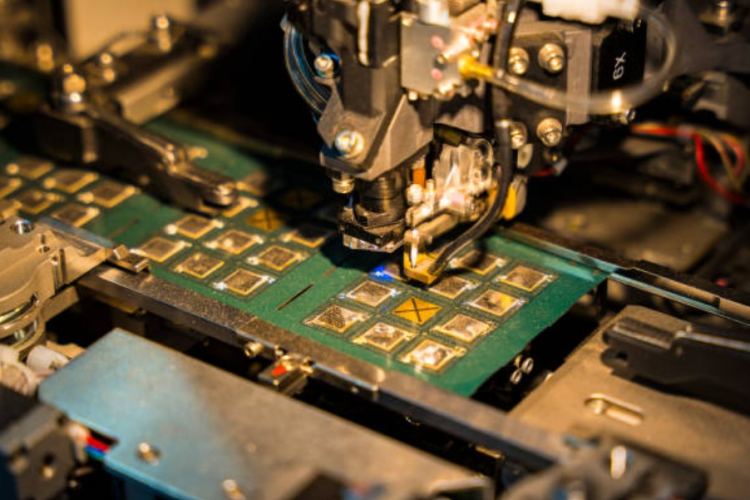

MeitY has approved investment proposals from five semiconductor-related companies—one for a fabrication unit, and four for ATMP/OSAT (assembly, testing, marking and packaging / outsourced semiconductor assembly and test) facilities. The approved firms include Micron Technology, Tata Electronics, CG Power, and Kaynes Technology.

Last year, three major semiconductor projects worth Rs 1.26 lakh crore were sanctioned. These included India’s first chip fabrication plant in Dholera, Gujarat, spearheaded by the Tata Group. The conglomerate also received approval for a Rs 27,000 crore assembly plant in Assam. CG Power’s Rs 7,600 crore ATMP facility in Sanand, Gujarat, was also cleared. India’s incentive scheme now covers all three critical legs of the semiconductor value chain—packaging (ATMP), assembly and testing (OSAT), and full-scale foundries.

Promising start, but challenges remain

Despite the momentum, India’s semiconductor ambitions face significant headwinds. A recent report by Jefferies outlines key hurdles: an underdeveloped supply chain, a shortage of skilled manufacturing talent, the fast-evolving nature of chip technologies, and fierce international competition.

While India boasts a robust pool of engineering talent and a global reputation in chip design—home to nearly 20% of the world’s semiconductor design workforce—it lags in critical areas. Most notably, the country lacks adequate access to essential raw materials such as silicon wafers, high-purity gases, specialty chemicals, and ultrapure water. These are non-negotiables for chip fabrication and currently must be imported, raising costs and vulnerabilities.

Skill gaps in advanced semiconductor fabrication and testing further limit India’s readiness. In contrast, countries like Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, China, and Malaysia have spent decades nurturing end-to-end semiconductor ecosystems. India is effectively playing catch-up in a field where time, experience, and scale are crucial.

To address this, the Indian government has prioritised building a comprehensive domestic supply chain. Regions such as Dahej in Gujarat already house advanced chemical and gas manufacturing capabilities, but producing semiconductor-grade materials remains a challenge. Policymakers are now exploring how to scale up this ecosystem to reduce import dependency.

Experts argue that no country fully controls the entire semiconductor value chain—some dominate minerals and raw materials, others excel in manufacturing, and a few in high-end tools and design. But unless India can plug critical supply and skill gaps, it will struggle to build a competitive foothold.

The technology treadmill

Another structural challenge is the pace of technological evolution. As India prepares to set up its first fabrication facility, global players are already working on next-generation nodes involving chip miniaturisation and higher processing power. As a late entrant, India will need deep and sustained capital investments just to keep up, let alone lead.

Building fabrication facilities—or fabs—also comes with high risks: unpredictable yields, quality assurance issues, and the pressure to quickly reach economies of scale. The sector’s long-term success in India will hinge on securing reliable demand, both domestically and through exports.

Meanwhile, geopolitical tensions and industrial policy shifts have intensified the global semiconductor arms race. The United States has launched ambitious subsidy programmes under the CHIPS Act. China, Taiwan, and South Korea continue to dominate, together accounting for about 70% of global chip production. Japan and the US share the remainder.

India cannot afford to be a spectator. As the global economic order becomes increasingly protectionist, the country must leverage its diaspora and seek strategic knowledge transfers. Indian-origin professionals working in global semiconductor firms are a rich source of intellectual capital that must be tapped more aggressively.

Foreign direct investment will also be key. To attract top-tier investors, India must address last-mile infrastructure challenges—ensuring reliable access to land, power, and water—and state governments will play a pivotal role here.

Learning from global playbooks

India can draw valuable lessons from other successful semiconductor ecosystems. Israel, for instance, has built a vibrant startup culture where technical talent, market insight, and corporate backing intersect. Israeli startups pursue global leadership, banking on agility and innovation.

China, by contrast, has pursued self-sufficiency—heavily investing in indigenous capabilities while protecting its domestic market. These divergent models show that success depends not on a one-size-fits-all strategy, but on national strengths and long-term commitment.

India, however, has long been a service hub for multinational tech giants, contributing heavily to design but creating limited proprietary IP. This service-driven model must evolve. To be a serious contender in the global chip race, India needs to build, not just design; to lead, not just follow.

The coming years will test India’s resolve. If it can combine policy ambition with execution discipline, align central and state efforts, and build robust partnerships with industry and academia, its semiconductor dreams could well materialise. But the clock is ticking.