It seems the Directorate General of Foreign Trade‘s notification last month which imposed restrictions on imports of laptops, tablets, Wi-Fi dongles, smart card readers, and other computer-related products has been put on the backburner. The notification on laptop imports restrictions issued on August 3 sent shockwaves through markets and industries. Rajeev Chandrasekhar, the minister of state for electronics and IT, clarified on September 26 that there would be no licensing regime for laptop and tablet imports, effectively overturning the DGFT notification. This policy reversal has left investors bewildered and raises questions about the government’s commitment to a stable and conducive business environment.

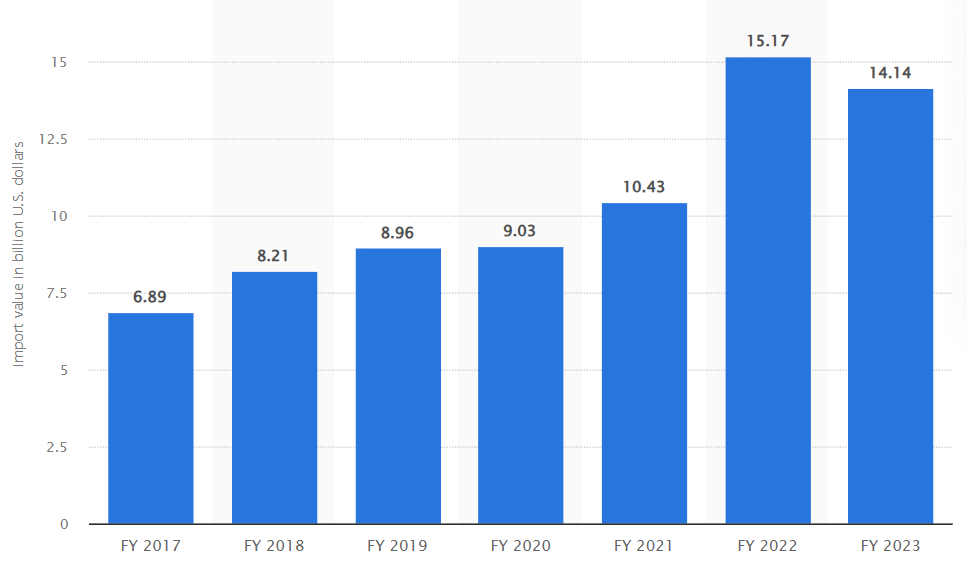

The DGFT’s initial notification had imposed restrictions on imports of laptops and computer-related products which amounted to $8.8 billion in the financial year ended March 2023. Under this notification, firms importing these products were required to obtain licences or permissions for imports beginning November 1, 2023. The sudden shift in policy has raised concerns about the consistency of the government’s stance on trade regulations.

READ I 5G and beyond: India’s spectrum allocation enter a new era

Govt allays fears about licensing regime

The minister attempted to clarify the government’s position at an event, stating that the DGFT notification was not communicated properly and that it was never intended to create a licensing regime, but rather an import management system. He also mentioned the forthcoming introduction of an Import Management System (IMS), which seeks to promote domestic manufacturing and ensure a trusted supply chain.

The details of how this system will operate are not available, leaving stakeholders in a state of uncertainty. Industry executives say the new monitoring system will require importers of laptops, tablets, and other hardware to register every year with the DGFT portal. The system will collect advance information including the source of imports.

Import value of computer hardware into India

While the government insists that there will be no import licensing, the proposed IMS, with its emphasis on domestic manufacturing and restrictions based on the geography of imports, effectively amounts to import restrictions. The lack of clarity surrounding the IMS raises concerns about its practical implementation, as it may require a complex and bureaucratic process that resembles an online import licensing system.

Furthermore, dragging the name of the Prime Minister into this debate over import regulations was avoidable. Most countries implement import restrictions based on their economic needs, and these decisions should be evaluated on their merits rather than invoking political figures.

Laptop imports is a tricky issue

It is essential for India to adopt policies that encourage domestic production of laptops and other electronics. The global dominance of China in the PC and laptop market, with an 81% market share valued at $130 billion in CY2022, poses a significant supply risk, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. India’s efforts to bolster local manufacturing of electronic devices are commendable but must go beyond incentivising superficial shell assembly companies.

The government’s wavering stance on import regulations sends mixed signals to both domestic and international investors. It may undermine confidence in India as a stable and consistent market. While global firms may express discomfort over import restrictions, it is essential for India, as one of the world’s leading economies, to make independent policy decisions aligned with its national interests. It is worth noting that other countries, including the United States and the European Union, have taken stringent measures to protect their interests in the face of evolving global dynamics.

The impact of the government’s flip-flop on laptop imports will also affect consumers. In the short term, it is likely to lead to higher prices and reduced choice for consumers, as importers scramble to adjust to the new regulations. This would spell trouble for students and other budget-conscious consumers, who may be forced to delay or forego purchasing a laptop altogether.

It confusion could also have a negative impact on innovation in the Indian electronics sector. By restricting access to imported components and technologies, the government may discourage domestic companies from investing in research and development. This could lead to a slowdown in the pace of innovation and make it more difficult for Indian companies to compete in the global market.

The flip-flop could also damage India’s trade relations with other countries, particularly China. China is the world’s largest producer of laptops and other electronics, and any restrictions on imports from China could lead to retaliatory measures from the Chinese government. This could harm Indian exporters and disrupt global supply chains.

India needs to adopt policies that encourage domestic production of laptops and other electronics. However, it is important to strike a balance between promoting domestic manufacturing and protecting the interests of consumers and businesses. The government’s flip-flop suggests that it is still struggling to find this balance.

It is also important to note that the global electronics market is highly competitive and dynamic. Domestic companies need to be able to access the latest technologies and components at competitive prices in order to compete effectively. The government’s import restrictions could make it more difficult for domestic companies to do this.

India must provide a clear and consistent policy framework to instill confidence in domestic and international stakeholders. Success in global trade demands a steady and reliable hand, and policymakers must prioritise long-term economic stability over short-term adjustments. India’s path to economic growth and technological advancement should be paved with stable policies that promote both domestic production and global competitiveness.

Anil Nair is Founder and Editor, Policy Circle.