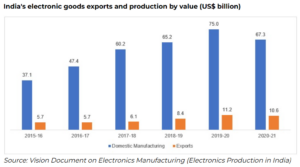

The Union government is poised to launch a Production-Linked Incentive scheme to stimulate electronics component manufacturing in the country, after the phenomenal success of the PLI scheme in smartphone manufacturing sector. Stakeholders have been requested to provide benchmarks that will inform the development of this incentive programme, as India seeks to catch up with the global leaders in this sector.

The ministry of electronics and information technology (MeitY) has initiated consultations with industry stakeholders as part of the 100-day agenda of the new government. These discussions are crucial as they will influence the budget allocation for the PLI scheme. The government has set an ambitious goal to elevate the component ecosystem to $75 billion with global scale capacities within just five years.

READ | How Amazon and Flipkart flouted anti-trust laws, crushed small businesses

PLI scheme in electronics component

The PLI scheme is the government’s flagship initiative designed to boost sectors deemed vital for India’s development and economic security. The success of the PLI scheme is largely attributed to its subsidy approach, which encourages a significant turnover from minimal capital investment. This approach has proven effective, particularly in mobile phone exports, significantly boosted by companies like Apple. While schemes targeting the green transition, batteries, and textiles have been launched, private investment in some sectors has lagged expectations, according to a review by an inter-ministerial panel.

The MeitY’s new programme will seek to replicate the mobile manufacturing success, aiming to increase domestic production of electronics components through an appropriate PLI-like scheme. For example, the semiconductor sector, which proved strategic during the pandemic, is now targeted for growth along with the non-semiconductor electronics part sector. The government is particularly encouraging higher participation from states like Tamil Nadu.

India in global electronics sector

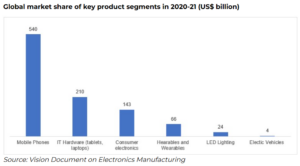

The global electronics sector is a $2 trillion industry, led by China which holds more than 50% market share. However, as wages in China rise, many companies are seeking to diversify their supply chains, presenting India with a significant opportunity to create the 200 million jobs it urgently needs. Despite this potential, India faces stiff competition; its electronics exports amounted to just over $23 billion in FY23, barely surpassing 1% of the global electronics trade. In contrast, smaller countries like Singapore, Vietnam, and Malaysia cumulatively export over $100 billion of electronics annually.

To successfully leverage the potential of the electronics manufacturing sector, India must significantly invest in research and development (R&D). The success of nations like South Korea and Taiwan in electronics is deeply rooted in their heavy investment in R&D, which fosters innovation and leads to the creation of high-value products. India needs to establish robust partnerships between academia, industry, and government to nurture an ecosystem conducive to cutting-edge research and technological advancements. This approach will not only enhance the technical competencies of Indian electronics but also elevate the nation’s standing in the global high-tech marketplace.

Challenges in components manufacturing

India’s electronics component manufacturing faces several challenges. Domestically, producers have a cost disadvantage of 18-22% compared with China and 9-11% compared to Vietnam, making competitive pricing difficult. Unlike mobile assembly, which is labour-intensive, manufacturing electronics component and sub-assemblies is capital-intensive, requiring substantial upfront investment to achieve economies of scale and global competitiveness. This has deterred potential investors and limited domestic production capacity. Additionally, the absence of a robust domestic market and challenges in securing contracts with OEMs have hindered participants in the PLI scheme for mobile devices from meeting production targets and claiming incentives.

Another area requiring immediate attention is skill development and workforce training. As the electronics sector evolves, so too does the need for a skilled workforce capable of handling advanced manufacturing processes and new technologies. The government must collaborate with educational institutions and private enterprises to create specialised training programmes that equip the Indian workforce with the necessary skills. This initiative will not only fill the current skill gaps but also boost job creation, providing the skilled labour needed to meet the demands of the electronics manufacturing sector.

The PLI scheme is not a panacea for underlying sectoral challenges, and they are not indefinite. Provisioning subsidies alone is insufficient; deeper policy reforms are necessary to make these sectors truly competitive. Instead of merely allocating large budgets for PLI schemes, the government should engage more actively with potential investors’ concerns and create more business-friendly conditions.

Analysts have also noted that while India has nearly 400 special economic zones (SEZs) aimed at boosting exports, they pale in comparison to China’s Shenzen SEZ in terms of size and output. To truly compete on the global stage, India should consider focusing on fewer, but larger and more competitive electronics clusters in strategic locations like UP (Noida), Tamil Nadu, and Telangana.

Currently, India holds a modest 3% share of the global electronics market. This underperformance is worrying as India seeks to shift from an import-reliant to an export-driven electronics economy. Comprehensive reforms in taxation, labour laws, and worker housing are essential. Without these radical changes, India may not fully capitalise on the vast opportunities in the global electronics market.