The Union Cabinet’s approval of the Unified Pension Scheme (UPS) is a major policy shift, addressing long-standing concerns of central government employees while looking to maintain fiscal discipline. Slated to take effect on April 1, 2025, this new scheme is set to benefit approximately 23 lakh central government employees, offering a blend of assured pensions and inflation-linked increments, along with enhanced security for their families.

The UPS emerges as a response to the demands of government employees for a stable post-retirement income, bridging the gap between the older, more secure pension systems and the market-linked National Pension System (NPS).

READ | Global trade: India’s stock rising amid uncertainties

Key features of UPS

The UPS offers several features that distinguish it from its predecessor, the NPS. The most notable is the guaranteed pension amount, which ensures that retirees will receive 50% of their last drawn salary, averaged over the final 12 months of service. This guaranteed pension is available to those with at least 25 years of service, while those with shorter tenures of 10 to 25 years will receive a proportionate amount. This contrasts sharply with the NPS, where the pension amount is tied to the performance of the investment portfolio, leaving retirees vulnerable to market fluctuations.

In a move designed to provide greater security to retirees, the UPS also introduces a minimum pension of Rs 10,000 per month for those who have served for at least 10 years. This feature is particularly beneficial for employees in lower salary brackets, ensuring a basic level of financial stability post-retirement.

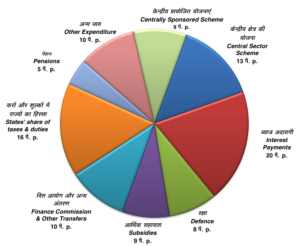

Summary of expenditure heads 2024-25

The UPS will also see the government’s contribution rising to 18.5% of an employee’s basic pay, up from the current 14% under the NPS. Employee contributions remain steady at 10% of basic pay and Dearness Allowance (DA). This increased government contribution is a clear attempt to bolster the pension corpus, providing a safety net that the NPS, with its reliance on market performance, could not guarantee.

Family security

One of the biggest grievances with the NPS has been the lack of assured family benefits. The UPS addresses this by guaranteeing that if an employee passes away, their family will receive 60% of the pension. This provision offers a level of financial security that was lacking under the NPS, where the family’s pension depended on the accumulated corpus and the annuity plan chosen at retirement.

Additionally, the scheme includes provisions for a lump-sum payment upon superannuation, calculated as one-tenth of the monthly emoluments (pay plus DA) for every six months of service. This payment is in addition to the gratuity, further enhancing the financial package available to retiring employees.

Fiscal implications and political calculations

While the UPS brings substantial benefits to government employees, it also carries significant fiscal implications. The government’s increased contribution will cost an estimated ₹6,250 crore in the first year alone. This figure includes ₹800 crore allocated for arrears owed to employees who have retired since the introduction of the NPS in 2004.

The timing of this scheme, ahead of crucial assembly elections and a general election, suggests a political dimension to its introduction. Government employees represent a vocal and influential constituency, and the UPS appears to be a strategic move to placate this group. However, this strategy comes with risks, particularly for state governments that might adopt the UPS model. The strain on state finances could be substantial, as highlighted by the Reserve Bank of India’s concerns about the potential accumulation of liabilities.

A hybrid approach

The UPS represents a hybrid approach, combining elements of the Old Pension Scheme with the contributory nature of the NPS. While the OPS was an unfunded, non-contributory scheme that guaranteed defined benefits, the NPS introduced a contributory, market-linked system with no guaranteed returns. The UPS seeks to offer the stability of the OPS, with assured pensions and family benefits, while maintaining the contributory, fully funded structure of the NPS.

This balanced approach is aimed at addressing the legitimate concerns of employees about income stability and security, without entirely reverting to the financially unsustainable OPS. By retaining the contributory aspect, the UPS attempts to mitigate the long-term fiscal burden that would accompany a full-scale return to the OPS.

The Unified Pension Scheme offers enhanced benefits and security to central government employees. However, it also raises concerns over the balance between providing adequate retirement benefits and maintaining fiscal prudence. While the UPS may satisfy immediate demands and yield political dividends, its long-term sustainability will depend on careful management of the associated financial burdens.

As state governments consider adopting this new scheme, they must weigh the benefits to their employees against the potential strain on their finances. The big concern here is the likelihood of the new scheme destroying the already strained fiscal positions of state governments. Bankrupt state governments can affect the growth potential of the Indian economy.

The success of the UPS will ultimately hinge on its ability to deliver on its promises without undermining the fiscal health of the government. In this sense, the UPS is as much a political statement as it is a pension reform, reflecting the ongoing challenge of balancing social security with economic sustainability in a changing India.