By Anmol Sehgal

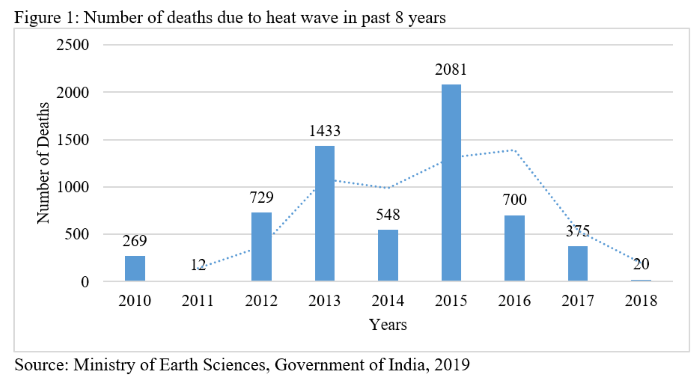

The year 2020 has been a particularly harsh one for India. The year started with the worst health emergency since independence, followed it up with the destructive cyclone Amphan and a severe heat wave across the north and north-west. The unexpectedly cold and rainy April gave way to a hot May. After the devastating cyclone, the winds over the Indian mainland became warmer without moisture content. Highest temperature was witnessed in Palam in the national capital area with mercury soaring up to 47.6 degrees. Heat waves in India can cause heavy destruction — 6,167 people lost their lives to summer heat between 2010 and 2018.

Over the past few decades, it has become apparent that human actions are causing changes in atmospheric composition, leading to the phenomenon of climate change. Human activities are changing the climate by increasing the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases. In its 4th assessment report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that, “the type, frequency and intensity of extreme events are expected to change as the earth’s climate changes, and these changes could occur even with relatively small mean climate changes.” The linear relationship between global warming and increase in mean temperature in India by over 0.5 degree Celsius in the last 50 years has been established scientifically by research studies across the nation and abroad and has also been verified by actual impact and the resultant loss of life. People who are repeatedly exposed to scorching heat or working in such weather conditions are exposed to greater threat of either falling ill or even dying.

READ: NASA maps to help measure snow cover over Arctic ice

India has witnessed a manifold increase in the human deaths during heat waves in years such as 1971, 1987, 1997, 2001, 2002, 2013 and 2015. The recently ended decade registered the highest number of deaths due to heat wave events compared with the previous three decades (MoES response to Parliament question, 2019). The Figure 1 shows the number of deaths due to heat waves during 2010-2018. As per the states tally, Andhra Pradesh reported maximum deaths of 1,422 of the 2015 total of 2,081, 100 of total 557 in 2016 and 236 of total 375 in 2017. Likewise, Telangana reported 584 deaths in 2015, 300 in 2016 and 100 in 2017 (ToI, 2019).

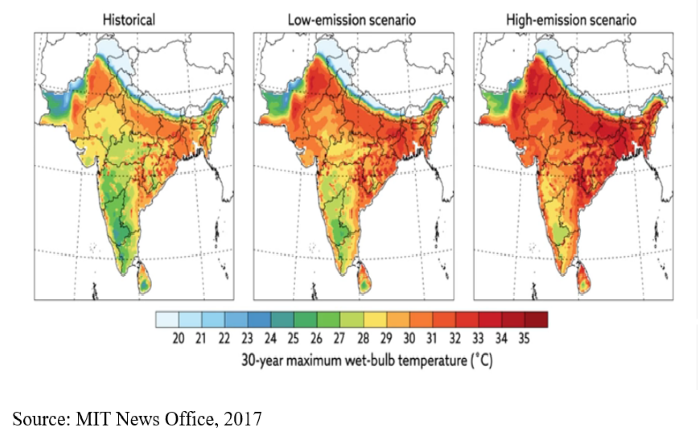

Researchers from MIT tried to forecast how Indian scenario would look like in low-emission vs high-emission and came up with startling findings. This new analysis is based on an index measured by a reading known as wet-bulb temperature which basically shows that hot weather has a deadly effect which comes from high temperature and humidity. Wet-bulb temperature of 35 degree Celsius (95 degree Fahrenheit), makes it impossible for the human body to cool itself and survival is difficult beyond a few hours. Figure 2 shows three scenarios stating how the temperature change will be witnessed across India with the northern and eastern parts being the worst affected.

The states that are expected to experience deadly waves in the red zone (Figure 2 — Odisha, Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh — account for a large chunk of the country’s poor and vulnerable population. The poor, mostly working as informal labourers in agriculture, construction and transport, can do very little to protect themselves from scorching heat. Even though official figures report a falling trend in casualties, year 2020 might be a bad year for the country with Covid-19 at its peak, lockdown relaxation, and migrant workers walking back to their villages.

Who are the worst hit

WHO says greater exposure to heat can lead to psychological stress that further worsens the health of people already facing respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. But some sections of the population that are either socio-economically or psychologically weak are extremely vulnerable. These people experience exacerbated illness, and an increased risk of death from exposure to excess heat. WHO says a large section of people including the elderly, infants, children, pregnant women, outdoor and manual workers, athletes, and the poor will be the worst affected.

READ: Indian agriculture needs a comprehensive strategy

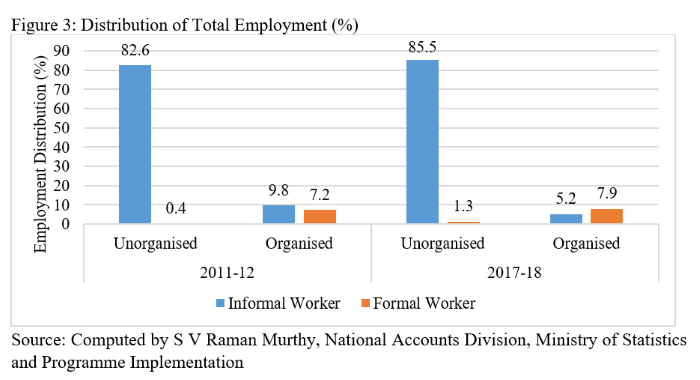

A country like India has larger problems to tackle. It has over 90% of the workforce in the unorganised informal sector (Figure 3) engaged as casual/ contract labourers working in agriculture, mining, and construction. They have maximum exposure to heat and sunlight with limited employment benefits and facilities. They work without adequate food and liquid intake that can affect their efficiency and health. But the plight of casual workers is that they have no option but to step out in the sun to earn a living. Along with this the agriculture produce also bears a major hit since most of the states in the red zone (Figure 2) are dependent on agriculture. If kharif crops sown in May to June and harvested in September to October encounter extreme changes in temperature, the output will be affected. Within Kharif, rice production is considerably affected with decreased grain yield which is a major concern as rice is a staple diet in many states experiencing heat wave. This further can increase the stress and vulnerability of the farmer and lead to foodgrain deficit in the country.

A double blow: COVID-19 and heat waves

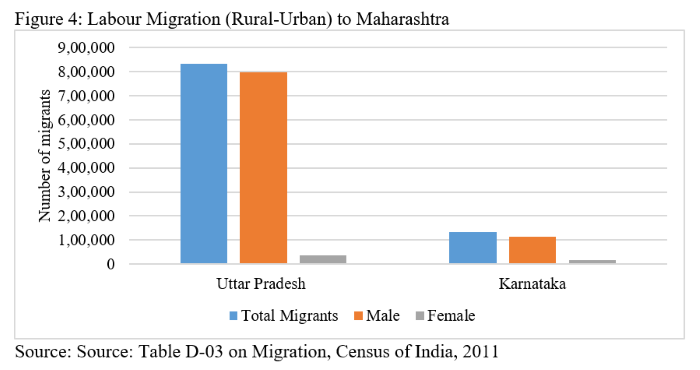

India is experiencing heat waves in parts of north and north-west at a time when lockdown is being relaxed. With schools and colleges being closed and private offices working on a rotational basis, a large number of the vulnerable people susceptible to heat waves have been saved. However, destitute migrants who work as casual/contract labourers in different parts of the country face the twin dangers of Covid-19 and the heat wave. Migrant workers are assembling in large numbers in Delhi, Maharashtra and some other states to get screened for Covid-19 and return to their homes via Shramik trains. They have been standing in long queues making it difficult to follow norms of social distancing. While waiting for their turn, many workers including women and children have talked to news reporters about their miseries of hunger, thirst and joblessness. According to an Indian Express report, more than 130 migrant workers died of exhaustion till May 18 while traveling back home by foot. With heat wave hitting India and migrant workers desperate to go back home, the number of deaths may surge.

It was common for manual labourers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to go to Delhi, Haryana and Maharashtra (Figure 4). However, labourers are now coming from Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan to metro cities. Among the biggest employers of migrant workers is the construction sector which accounts for 9% of the GDP with 40 million workers followed by domestic work (20 million), textile (11 million) and brick kiln work (10 million). These casual labourers are the worst sufferers of the heat wave and Covid-19 as they have no access to proper sanitation.

Are government provisions enough?

In the beginning of the lockdown, the government had set up relief camps for workers from different regions to provide them shelter and food. In an affidavit dated April 12, Union home secretary Ajay Kumar Bhalla stated that 37,978 relief camps are set up for migrant labourers by the various states, Union territories and NGOs. He also added that 14.3 lakh people have been given shelter in them. Additionally, 26,225 food camps have been opened to provide food to nearly 1.34 crore people. The task was gaining slight momentum with workers complaining of no food or water facility. The metal roofs of the shelter homes will make it difficult to protect people from the scorching heat.

Even after the easing of the lockdown and resumption of construction activities with workers residing in the same city, things have not taken off due to excessive heat and paucity of means to protect workers from the harsh climate. An ILO report on Covid-19 has predicted that as a result of the Covid-19 crisis and the lockdown measures, around 400 million workers will fall deeper into poverty, forcing many of them to return to their homes in rural areas. This roughly makes 400 lives exposed not only to the pandemic, but also to devastating weather conditions and vicious poverty. There is a high chance of workers who have already started working catching fever and heat strokes. With Covid-19 having undistinguishable symptoms of fever, headache, pains, a normal fever could create unwanted panic and fear among the people living in shelter homes or on-site facilities.

READ: The digital divide: Why Kerala is not ready for the online education plunge

In the past, the government has taken several steps to mitigate the pain of heat waves. As an adaptive measure, Indian Meteorological Department had started a “heat action plan” in many parts of the country in collaboration with local health departments to warn in advance and help people survive extreme situations. The main objectives of the heat action plan are “building public awareness and community outreach, utilizing early warning systems and inter-agency coordination, capacity building among healthcare professionals and reducing heat exposure and promoting adaptive measures” (MoES 2019). Unfortunately, the Union government has officially refused to declare heat waves as natural disasters.

Exclusive provision for workers for their protection is still not in place. This year, India needs to have a completely different policy framework where there is provision for protection of workers from disease and weather. The situation at hand needs to be addressed in a systematic manner. Apart from shelter facility for migrant workers, there should be provision for cold drinking water and liquids like energy drinks at the shelters. Apart from this, workers starting their daily tasks at various locations should be given basic amenities like water coolers, masks and gloves for protection from the heat and the virus. Lastly, Ayushman Bharat scheme should contain provision for treating workers falling ill due to heat waves as it has been made for Covid-19 treatment.

(Anmol Sehgal is a research assistant with the Centre de Sciences Humaines, New Delhi)