The images of the great Indian migrant exodus are fresh in the memory of the nation. Migrant workers came in droves to Anand Vihar Bus Depot in East Delhi on March 28, 2020, following a rumour that transport is being provided to people traveling to the eastern and central Indian states. They waited patiently with discipline for more than 36 hours and then started walking to their villages. Millions of people walked silently with their families and all their worldly possessions without any protest. The sudden declaration of the nation-wide lockdown to stop the spread of Covid-19 pandemic forced nearly 100 million migrant workers in different cities to hit the street in a state of absolute uncertainty.

This great human tragedy unfolded in the last week of March brought to the fore the plight of millions of workers in the unorganised sector in the country. They did not have able leaders and trade unions to engage in collective bargaining and conduct negotiations with their employers and the state. Years of neoliberal policies have weakened India’s labour/ trade unions through a process of informalisation of the work place and workers. The labour laws were relaxed in favour of employers, and the image of trade unions took a beating. The exodus during Covid-19 lockdown exposed the vulnerability of workers in India in the absence of trade unions. They were pushed to the corner after a gradual, but systematic decimation of trade unions.

READ I Returning migrants: Big trouble awaits Covid-hit Kerala economy

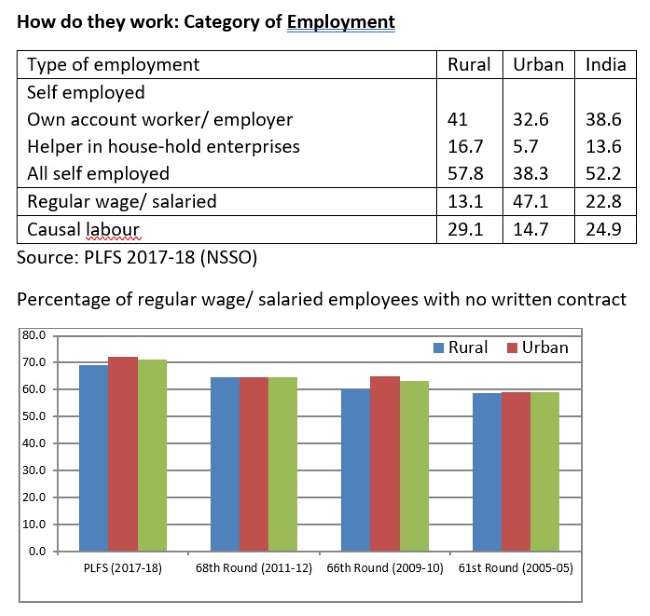

According to the Participation of Labour Force Survey 2017-18, 38.3% of the employed people in urban India are self-employed and 14.7% are causal labourers. The numbers for the entire country are 52.2% and 24.9%, respectively. This means 77% of working Indians are on their own in the labour market. Out of the regular wage/ salaried people, more than 71% work without a contract, 55% do not have paid leave, and 50% do not have any social security support. This explains how vulnerable they are and why they cannot organise for their rights. In the last decade, there has been a sharp rise in non-contractual regular jobs in India. They function in the formal sector as informal workers. When the lockdown was declared, employers were not obliged to provide support to their staff. This explains the worker exodus that unfolded during the lockdown.

The Participation of Labour Force Survey goes on to explain that almost two thirds of those who work as regular employees are service workers employed in shops, craft and related trades, and support workers in the formal sector. They become jobless when the economic activities stop. Most of those in the unorganised sector are engaged in construction, manufacturing supply chains, household support work, restaurants, shops and sanitation work, while some are street vendors or owners of micro units.

The lockdown was rolled out in an unplanned manner. The workers in the unorganised sector failed to collectively bargain with the government for transportation facilities. Without the power to assert their human and labour rights, they were left at the mercy of the state and charity of others for food, water, stay and transport. Simply, the system converted informal workers into beggars and forced them to walk to their homes hundreds of kilometers away.

READ I Honey I shrunk the middle class, killed the Indian economy

During the time, some Indian states suspended labour laws that ensure the dignity of workers. Many Indian private enterprises announced massive layoffs and salary cuts. The institution that worked to provide dignity to workers — trade unions – was either absent or absolutely ineffective during the entire crisis.

Trade unions: Growth and coverage

The post-reform period saw the informalisation of production activities in India. More jobs were generated outside factories. Since people working from home were not connected to each other, unionisation of workers became difficult. Out of the jobs generated in India during 2017-18, 80-90% were in unorganised sector. This sector contributes nearly 40% of the GDP and 90-95% of the total private sector employment in India. Demonetisation and GST rollout had impacted the workers adversely. The Covid-19 lockdown aggravated their hardships and pushed them into poverty.

READ I India must prepare for a bout of migration by doctors, medical staff

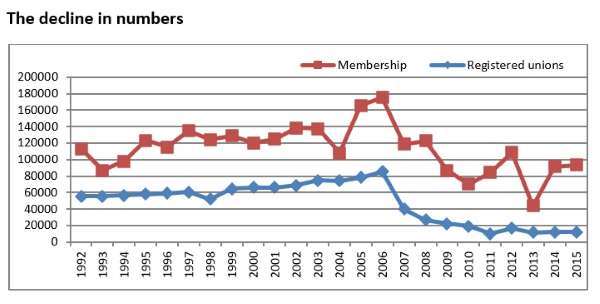

Over the last 30 years, a few deliberate and some accidental interventions by various agencies rendered the trade unions powerless. According to the National Labour Bureau, the number of registered trade unions in India fell from 55,680 in 1992 to 12,486 in 2014. The decline was dramatic since 2006. Union membership fell from 5.7 million in 1992 to 3.4 million in 2004, but thereafter rose steadily to 8 million in 2015. Only 1.7% of the total workers in both the formal and informal sectors were part of a labour organisation in 2015.

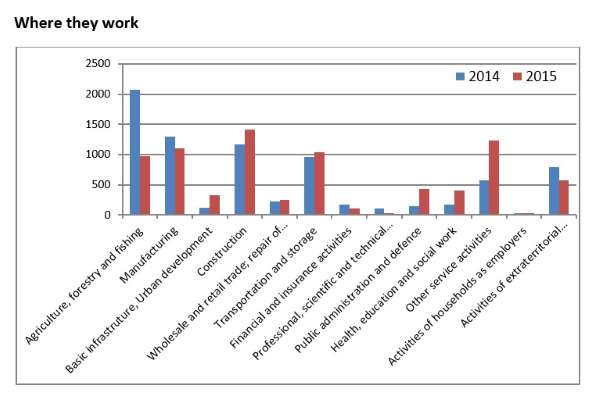

Data from different sources explain how badly labourers are organised. While 60% of trade union members are in the formal sector and among them a majority are with public sector. The rest of the union members are in informal sector that constitute more than 90% of the total workforce. Therefore, only less than 0.5% of informal sectors worker have membership in trade unions. In the informal sector, trade union members are mainly engaged in agriculture, construction, transportation and storage sectors. Other sectors have very few trade union members.

Further, most of the trade union members in India are from two states — Kerala (32%) and Assam (25%). Kerala and Assam together have only 5% of the total workforce in India, but they have 57% of the trade union members in the country. The trade unions are either absent or powerless in India’s major industrial hubs such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Telangana and West Bengal. They are also absent in major agricultural and mining centres such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh. About 36% of the trade union members are in agriculture and allied activities. Only a small fraction of workers in non-agriculture sectors are organised.

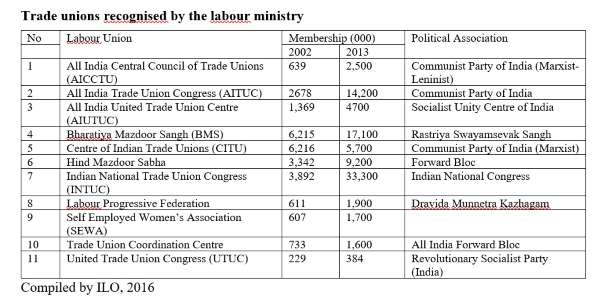

Many of the trade unions in India are affiliated to political parties such as the BJP, Congress and Communist parties, still they are powerless to protest the shoddy treatment of workers. So, an event that could have resulted in a nation-wide labour unrest, went without a whimper in India. In the absence of trade unions, the state needs to go the extra mile to mitigate the sufferings of the country’s vulnerable working class.

(Dr Resmi Bhaskaran is a development economist based in Manipal, Karnataka. The views are personal.)

Policy Circle is now on Telegram. For analysis & opinion on economy, policy, governance and more, subscribe to policycircle on Telegram.

Resmi Bhaskaran is a development economist based in Manipal, Karnataka.