Ageism has been identified as a critical barrier to promoting digital equity and healthy ageing and geriatrics care (WHO 2021). In the next three decades, the number of older people worldwide is projected to double, reaching over 1.5 billion in 2050. Unless policies and programmes are in place, a significant percentage of older persons are likely to experience poor health outcomes and negative social and economic consequences due to the all-pervasive practice of Ageism.

The theme of International Day of Older Persons 2021 is ‘Digital Equity for All Ages: A Global campaign to combat Ageism in the digital age.’ The United Nations designated the International Day of Older Persons to highlight the unique contributions that older people make to society and explore the issues and challenges of ageing. The International Day of Older Persons 2021 also establishes the older persons’ need for access and meaningful participation in the digital world. The objectives of UNIDOP2021 are:

- To address digital availability and innovation in the areas of public and private interests.

- To bring awareness of the importance of digital inclusion of older persons.

- Tackling stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination associated with digitalisation.

- To highlight policies to leverage digital technologies for full achievement of the sustainable development goals (SDGs).

- To explore the role of policies and legal frameworks to ensure the privacy and safety of older persons in the digital world.

- To promote an intersectional person-centred human rights approach in the field of digitalisation.

READ I Online education: Long-term vision needed to bridge digital divide

International Day of Older Persons: The context

Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years will rise from 12% to 22%. By 2020, the number of people aged 60 years and older outnumbered children younger than five years. In 2050, 80% of older people will be living in low- and middle-income countries. The pace of population ageing is much faster than in the past. As a result, all countries face significant challenges to ensure that their health and social systems are ready to make the most of this demographic shift.

People worldwide are living longer. Today, most people can expect to live into their 60s and beyond for the first time in history. Longevity brings with it opportunities for older people and their families and societies as a whole. Additional years provide the chance to pursue new activities such as further education, a new career or pursuing a long-neglected passion.

Older people also contribute in many ways to their families and communities. However, the extent of these opportunities and contributions depends heavily on one factor — health. With appropriate policy and programme interventions, there is an opportunity to harvest the benefits of a second demographic dividend — the demographic benefits of healthy older persons.

READ I Labour reforms: What do the four labour codes mean to businesses, workers

Intersectionality of ageism and digital exclusion

The intersectionality of ageism and digital exclusion is a challenging social phenomenon, needs close analysis and action propositions. Digital exclusion is a day-to-day reality of many older persons. As a result, older persons are systematically excluded from the benefits of digital expansion. According to UN DESA, Digital technologies refer to a wide range of new technologies ranging from the internet, mobile phones, and other digital tools to collect, store, analyse, and share information.

Though PCs and Laptops are widely available, older persons daily encounter a range of digital technologies, which they may not have mastery of. Moreover, the digital landscape is vast and complex. This could intimidate even a techno-savvy young person. While older persons are increasingly connected digitally, most are unaware of the digital risks. Cybercrimes targeted at older people new to the digital world, misinformation that threatens older people’s health, well-being, human rights, privacy, and security are new cyber challenges older persons have to deal with.

Natalina Martiniello, Leila Haririsanati & Walter Wittich (2020) identified a range of enablers and barriers encountered by working-age and older adults. Digital inclusion is an enabler for the older population.

READ I TechFins: Why India must stop their unregulated, untaxed run

Creation of stereotypes

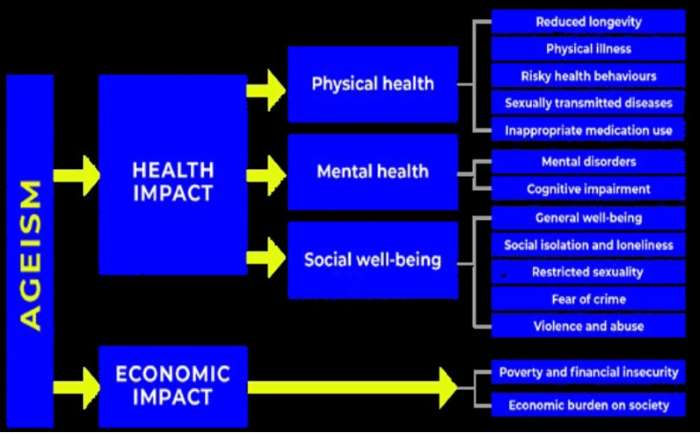

Ageism is a complex phenomenon. It is a process of creating stereotypes of how we think, feel, and act towards others or ourselves based on age. Moreover, ageism is a global phenomenon with serious health, social, and economic consequences for individuals and society. According to a WHO report (WHO2021), ageism is everywhere, yet it is the most socially normalised and accepted form of prejudice and is not widely contradicted like racism or sexism.

Ageism is displayed when the media portrays all old people as frail and dependent. The idea of ageism influences (passively or proactively) the policymakers to shift the cost to make appropriate adaptations and investments in infrastructure and services for promoting equity in healthy ageing and geriatrics care.

The discriminatory attitude towards older people is pervasive yet invisible, leading to the marginalisation of older people within their communities and negatively impacts their health and well-being. According to the UN Global Report on Ageism, half of the world’s population demonstrate ageism against older persons. Moreover, the Covid-19 pandemic brought to light deep-rooted ageism and age discrimination in health care and social welfare systems.

The UN Secretary General’s policy brief on Covid-19 and older persons recognised that Covid-19 escalated ageism and stigmatisation of older persons, including hate speech in public discourse and social media. The policy brief further presented a range of particular risks for older persons. Although all age groups are at risk of contracting Covid-19, older persons are at a significantly higher risk of mortality and severe disease following infection. An estimated 66% of people aged 70 and over have at least one underlying condition, placing them at increased risk of a severe impact from Covid-19.

Older persons may also face age discrimination in decisions on medical care, triage, and life-saving therapies and diagnostic support. Even before the pandemic broke out, as many as half of older persons in some developing countries did not access essential health services. The pandemic may also lead to a scaling back of critical services unrelated to Covid-19, further increasing risks to the lives of older persons.

Often the roots of exclusion of older people are in ageism. Ageism arises when age is used to categorise and divide people, with a view to exclusion, harm, disadvantage, injustice, and erode solidarity across generations. , Ageism damages our health and well-being and is a significant barrier to enact effective healthy and active ageing policies and actions (WHO 2021).

The report of the UN Independent Expert on the enjoyment of all human rights by older persons to the 48th session of the UN HRC (A/HRC/48/53) examined and raised awareness of the prevalence of ageism and age discrimination, analysed their possible causes and manifestations. This report also reviews how the existing legal and policy frameworks at the international and regional levels protect against ageism and age discrimination.

According to the independent UN expert on the enjoyment of all human rights by older persons Claudia Mahler (2021), little attention has been paid to the barriers experienced by older persons. The barriers include not seeking effective redress and remedies, despite reports of care homes worldwide showing neglect, isolation and lack of adequate services.

Reports of increases in gender-based violence and higher risks of violence, abuse, and neglect of older persons confined with family members and caregivers due to lockdown measures are exasperatingly high. Claudia Mahler further highlighted that entrenched ageist attitudes hinder older persons from claiming their rights and undermine their autonomy and called as a matter of urgency for access to justice by older persons.

Older people who feel they are a burden may also perceive their lives to be less valuable, putting them at risk of depression and social isolation. For example, Levy et al. (2002) research shows that older adults with negative attitudes about ageing may live 7.5 years less than those with positive attitudes. Technological advances offer great hope for accelerating progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, one-half of the global population is offline, with the starkest differences reflected between most and least developed countries (87% and 19%, respectively) (ITU 2019).

The most excluded populations are an older segment of the population and older women in particular. Unfortunately, technological innovations have seldom paid attention to the need to include the older population in their consumer base. Instead, the architect of the modern technological advances keeps the affluent younger population as their client base.

Although some of the variations in older people’s health are genetic, much is due to physical and social environments. Often these are structurally determined by society. Access to safe homes, neighbourhoods, communities, and their ethnicity or socioeconomic status are determined by social structures. Social structural factors also influence digital inequity. Structural reform and structural changes are often essential to ensure access to more significant digital equity.

Recent reports by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) indicate that women and older persons experience digital inequity to a greater extent than other groups in society; they either lack access to technologies or are often not benefitting fully from the opportunities provided technological advancement. The Secretary-General’s Roadmap (2020) seeks to address these challenges by recommending concrete action to harness the best of these technologies and mitigate their risks.

If people can experience these extra years of life in good health and live in a supportive environment, their ability to do what they value will be slightly different from that of a younger person. However, if these added years are dominated by a decline in physical and mental capacity, the implications for older people and society are more pessimistic.

According to WHO, Ageing leads to a gradual decrease in physical and mental capacity, a growing risk of disease, and ultimately, death. But these changes are neither linear nor consistent, and they are only loosely associated with a person’s age in years. Thus, while some 70-year-olds enjoy extremely good health and functioning, other 70-year-olds are frail and require significant help from others.

Beyond biological changes, Ageing is also associated with other life transitions such as retirement, relocation to more appropriate housing, and the death of friends and partners. Thus, in developing a public-health response to ageing, it is essential to consider approaches that ameliorate the losses associated with older age and those that may reinforce recovery, adaptation, and psychosocial growth.

As people age, they are more likely to experience several conditions at the same time. These are commonly called geriatric syndromes. Geriatric syndromes appear to be better predictors of death than the presence or number of specific diseases. The challenges in responding to population ageing and exclusion are; diversity in older age, health inequity, ageist stereotypes, and the rapidly changing world, characterised by globalization and rapid technological developments.

There is no typical older person. Some 80-year-olds have physical and mental capacities similar to many 20-year-olds. The diversity seen in older age is not random. A large part arises from people’s physical and social environments and their impact on their opportunities and health behaviour. Older people are often assumed to be frail or dependent and a burden to society. However, globalisation, technological developments (e.g., in transport and communication), urbanisation, migration and changing gender norms are influencing the lives of older people in direct and indirect ways.

Global response to ageism

Some significant multilateral responses are emerging to address the concerns of a rapidly ageing population. Political Declaration and Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (2002), Berlin Ministerial Declaration (2002), Proclamation of Ageing (1992), United Nations Principles for Older Persons (1991), Vienna International Plan of Action on Ageing (1982) and WHO Decade of Healthy Ageing (2020-2030) are some such responses. Commitment to healthy ageing requires awareness of the value of healthy ageing and sustained commitment and action to formulate evidence-based policies that strengthen the abilities of older persons.

Health systems need to be better organised around older people’s needs and preferences, designed to enhance older people’s intrinsic capacity, and integrated across settings and care providers. Systems of long-term care are needed in all countries to meet the needs of older people. This requires developing, sometimes from nothing, governance systems, infrastructure and workforce capacity.

Creating age-friendly environments will require actions to combat ageism, enable autonomy, and support healthy ageing in all policies and government levels. In addition, improving access to assistive digital technologies are likely to improve the ageing outcome.

(Dr Joe Thomas is Professor of Public Health, Institute of Health and Management, Victoria, Australia. Opinions are personal.)

References:

UN DESA, Political Declaration and Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (2002)

The United Nations Secretary-General (2020) Roadmap for Digital Cooperation. 11 June 2020, (A/74/821).

ITU (2019) Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2019.

Massimo Ragnedda (2020) Enhancing Digital Equity: Connecting the Digital Underclass. Springer Nature, 2020. ISBN 3030490793, 9783030490799

WHO. Ageing and health.

Natalina Martiniello, Leila Haririsanati & Walter Wittich (2020): Enablers and barriers encountered by working-age and older adults with vision impairment who pursue braille training, Disability and Rehabilitation.

Dr Joe Thomas is Global Public Health Chair at Sustainable Policy Solutions Foundation, a policy think tank based in New Delhi. He is also Professor of Public Health at Institute of Health and Management, Victoria, Australia. Opinions expressed in this article are personal.