ASHA workers for Kerala: As the global health community prepare to mark World Health Day 2025 under the theme ‘Healthy Beginnings, Hopeful Futures’, attention has turned to the critical importance of maternal and new-born health. Despite progress, global trends suggest that 80% of countries remain off track to meet maternal survival targets by 2030, while a third are likely to miss new-born death reduction targets. Kerala, often cited as a model for public health in India, continues to report the country’s lowest maternal mortality ratio at 19 per 100,000 live births.

Recent indications of a rising MMR highlight the need for renewed attention to foundational elements of Kerala’s healthcare delivery system—chief among them, the largely unsung efforts of its community health workers, the ASHAs. Addressing their concerns is no longer just a matter of equity; it is essential for sustaining Kerala’s maternal and child health outcomes.

READ | Data, chips and sovereignty: Towards a new world order

The role of ASHA workers

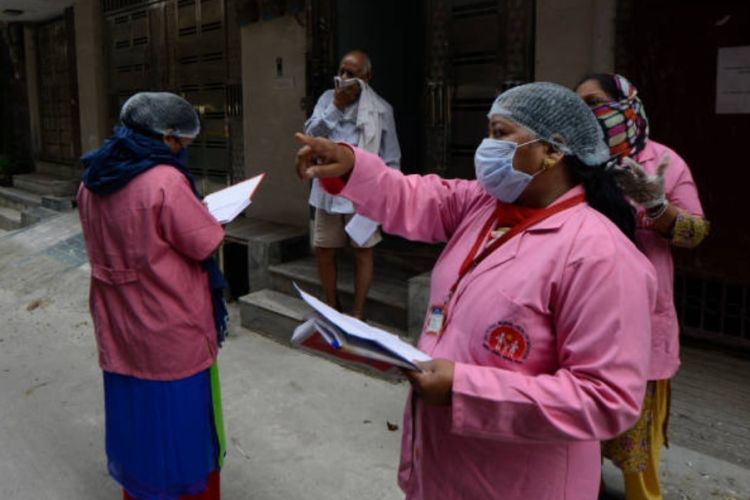

ASHA workers are not passive assistants; they are the first responders, community educators, mental health counsellors, maternal care companions, and public health foot soldiers rolled into one. They escort pregnant women to health centres at all hours, facilitate immunisation drives, ensure compliance with antenatal and postnatal protocols, and provide vital health education in every hamlet. A recent study has mapped their functions to over 30 distinct health-related tasks, many of which are critical for maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Their impact is visible in the metrics. Kerala’s progress in reducing infant and maternal mortality owes much to the vigilance and grit of these women. But even as the public system leans heavily on them, ASHAs are being squeezed dry.

Kerala’s ASHA workers are on a prolonged agitation with a list of 20 demands—none of them unreasonable. The core demand is recognition: as full-time workers, not volunteers to be discarded at 62 without retirement benefits. The demand for a retirement package of Rs 5 lakh, similar to what West Bengal offers, is not a drain on the exchequer—it is an investment in workforce morale.

To ignore these demands is to jeopardise Kerala’s maternal and child health gains. The state can’t wish away the ASHA; without her, its health architecture will crumble. What’s worse, these workers face invisible battles that compound the injustice of poor pay.

The irony is bitter. The state expects ASHAs to be the bridge between pregnant women and institutional deliveries, the shield against infant mortality, the voice of sanitation, immunisation, and contraception. But the same state does not offer them legal protection, minimum wages, or even timely payment for extra surveys and pulse polio duties. Here lies the policy paradox. Kerala, a state with one of India’s highest human development indices, is treating the backbone of its primary health system as an afterthought.

Globally, the role of community health workers (CHWs) is being re-evaluated. In South Africa, ward-based primary care teams are built around six CHWs, supported by trained nurses and environmental officers. Rwanda, Bangladesh, and even Brazil have adopted models where CHWs are given structured training, performance-based incentives, and institutional support. India, too, must walk that path—starting with Kerala.

The WHO has been unequivocal: CHWs are essential to achieving universal health coverage. But they cannot do their job without clarity of role, proper training, and dignity of labour. Kerala’s ASHAs are educated, experienced, and embedded in the community. Their shift from volunteers to de facto full-time workers through task shifting needs to be matched with institutional recognition.

This requires more than token gestures. The government must immediately:

- Declare ASHAs as formal public health workers under the health department.

- Provide them with monthly minimum wages, beyond the current Rs 9,000 (of which the Union government provides just Rs 2,000).

- Extend social security, health insurance, and retirement benefits.

- Institute zero-tolerance policies against workplace violence and offer mental health support.

- Integrate their voices into policy planning—ASHAs should be on health advisory panels and district health committees.

Beyond the paperwork, a cultural reset is needed. The public must be educated about the pivotal role of ASHAs. Panchayats must stop using them as cheap labour for political events. Hospitals must treat them as colleagues, not errand-runners.

Kerala is at a fork in the road. It can either lead the way by formalising and empowering its community health workforce or risk losing the gains that took decades to achieve. The MMR graph does not lie. Neither does the exhaustion in the eyes of a 45-year-old ASHA who has just delivered her third baby to the district hospital after walking five kilometres and soothing the anxious mother for hours.

On World Health Day 2025, when the world is talking about hopeful futures and healthy beginnings, let Kerala not forget who brings hope and health to its villages. It’s time to stop romanticising the ASHA as a selfless caregiver and start treating her as what she really is—the engine of primary health care.

And engines, unlike slogans, require fuel. Not just the fuel of purpose—but of policy, pay, and protection.

Dr Joe Thomas is Global Public Health Chair at Sustainable Policy Solutions Foundation, a policy think tank based in New Delhi. He is also Professor of Public Health at Institute of Health and Management, Victoria, Australia. Opinions expressed in this article are personal.