The discovery of microplastics and nanoplastics in human organs, including the brain, has ignited concerns about the potential health implications of this growing environmental crisis. Recent studies confirm the presence of microplastic particles in human kidneys, livers, and particularly the brain, raising urgent questions about their long-term impact on human health.

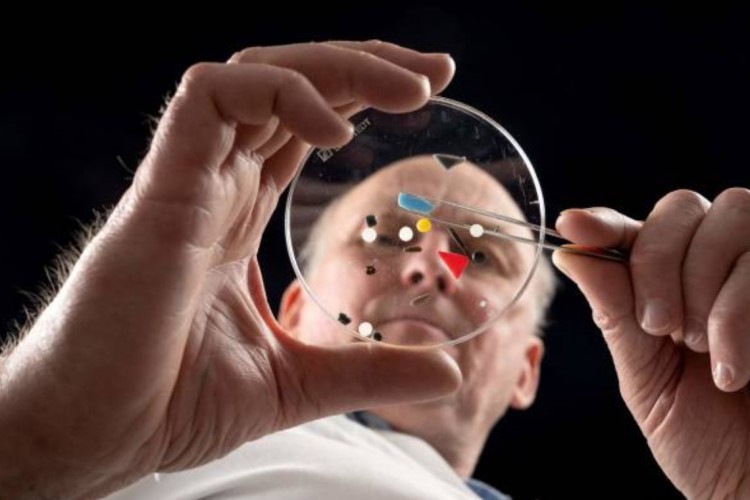

Microplastics, defined as plastic particles smaller than five millimetres, have infiltrated the environment on a massive scale. From the deepest oceans to fresh Antarctic snow, their omnipresence is now evident. A landmark study by toxicologist Matthew Campen and his team at the University of New Mexico has revealed startling data: human brain tissue can contain up to 10 grams of microplastics, equivalent to the weight of an unused crayon. Notably, microplastic concentrations in brain samples have increased by 50% from 2016 to 2024.

READ | Foreign debt: Weakening rupee is squeezing corporate India

Microplastics in human brain

The presence of plastics in the human body is not uniform. The recent study published in Nature Medicine shows that brain samples contain up to 30 times more microplastics than liver or kidney samples. Additionally, a study using autopsied human tissues found that polyethylene (PE) is the most prevalent type of plastic in brain tissue, primarily in the form of nanoscale shards. These findings signal an alarming increase in human exposure to plastic pollution and its possible bioaccumulation in the body.

The routes through which microplastics reach human organs are varied and complex. While ingestion through contaminated food and water remains a primary concern, inhalation has emerged as an even greater threat. Studies indicate that airborne microplastics can be inhaled and travel deep into lung tissue, potentially entering the bloodstream and eventually accumulating in the brain.

Animal studies suggest that microplastics can cross biological barriers, including the blood-brain barrier, which typically prevents harmful substances from reaching the brain. Experiments on mice have shown that microplastics consumed via drinking water were absorbed by immune cells, which then transported them through the bloodstream. In the brain, these plastics were found to accumulate in and block small blood vessels, raising concerns about their potential link to neurodegenerative diseases.

Questions on health implications

Despite accumulating evidence, scientists are still grappling with the exact consequences of microplastics on human health. Laboratory studies have demonstrated that microplastics can induce cell death, trigger inflammatory responses, and cause tissue damage. Their presence in the brain, in particular, raises concerns about their role in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. In a separate study, brain samples from individuals with dementia were found to contain significantly higher concentrations of microplastics than those without the condition.

Moreover, microplastics have been linked to cardiovascular issues. A landmark study published in March 2024 found that individuals with microplastics in their arteries were 4.5 times more likely to suffer from heart attacks, strokes, or death within three years of heart surgery. However, researchers caution that while the data shows a correlation, it does not yet confirm causation.

Challenges in understanding full impact

One of the biggest challenges in studying microplastics’ health effects is the lack of standardised testing methods. Different scientific teams use various techniques to detect and analyse microplastics, leading to inconsistencies in data collection and interpretation. Additionally, many laboratory studies rely on pristine microplastic spheres, which do not accurately represent the diverse shapes and compositions of plastics found in the environment.

Another critical issue is the difficulty in detecting nanoplastics—particles smaller than one micrometre. These tiny fragments can penetrate cells and tissues, yet current imaging and detection techniques are not advanced enough to reliably track them. This limitation means that existing studies might be underestimating the extent of microplastic accumulation in the human body.

Policy implications and need for action

With plastics production reaching record levels each year, the burden of microplastics on human health is only set to worsen. According to projections, global plastic production could more than double by 2050, leading to an exponential increase in microplastic pollution. Even if production were halted today, existing plastics in the environment—estimated at five billion metric tonnes—would continue to degrade into microplastics for centuries to come.

Recognising this growing crisis, policymakers and researchers are pushing for global regulations on plastic production and disposal. The United Nations is currently negotiating a treaty to curb plastic pollution, which could introduce caps on global plastic production. However, achieving a consensus on such measures has proven difficult, and delays could have lasting health consequences.

Some scientists argue that while research continues, immediate action is necessary. Strategies such as reducing plastic consumption, banning single-use plastics, and improving waste management can help limit human exposure to microplastics. Meanwhile, advancements in microplastic detection and filtration technology in water and air purification systems could mitigate some risks.

The infiltration of microplastics into human organs, particularly the brain, poses a serious and growing threat to public health. While researchers are still working to determine the exact health consequences, the sharp rise in microplastic accumulation in human tissues should serve as a wake-up call. As studies continue to refine detection methods and understand microplastic toxicity, the need for immediate policy action to curb plastic pollution has never been more urgent.

If left unchecked, microplastics could become one of the most significant environmental health crises of our time. The question is not just whether they are harmful, but how much damage has already been done—and how much more we are willing to tolerate.